This week’s question deals with the navigational tool of Danger Bearings. Congradulations to Brian H, for getting the answer correct. Several people posted they wouldn’t allow themselves to get this close to possible danger.

I agree, except that this situation is no different than what we encounter entering many harbors in the Caribbean, The Bahamas or for that matter many places right here in the US like Maine, unmarked dangers close to our course or in narrow passages that just are not marked. Sailing in most places outside the US markers for hidden dangers either don’t exist or are unreliable. I’ve entered and left many a harbor in the Bahamas using Danger Bearings and a handheld compass to avoid submerged dangers either side of an entrance and I’ve used them to avoid dangers along my course as I have navigated the rock-strewn waters of Maine. Not all dangers even on US charts have buoys on them, to do so would be cost prohibitive so it just isn’t done.

So we have our question, “how to insure you avoid the 2’ rock using a handheld compass”.

In this week’s question you were sailing from Sachems Head to Faulkner’s Island on a course of 133°m with the tide flooding (from east to west). You are concerned that the tide and depending on which tack you are on, leeway, might push you off course and possibly hit the 2’ rock that is about ¼ nm south of the rhumb line, a very real possibility even if you have adjusted your course for current using a current vector.

There are two methods we could employ here, both involve the use of a handheld compass. The first method, take a bearing every now and then on the light house and as long as it is within a couple degrees of 133°M you are standing clear of both the 2’ rock south of the rhumb line and the breakwater just to the east of the rhumb line.

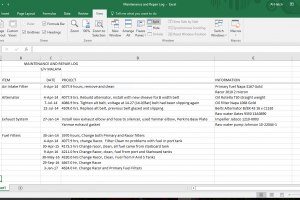

Chart 1 showing our Rhumb Line of 133°M and a Danger Bearing of 120°M

Another slightly more involved method involves drawing a line on the chart from a visible landmark or Aid To Navigation (ATON) a safe distance past the danger we wish to avoid. This line is called a “Danger Bearing”. (See Chart 1)

In our case here we would use the Light on Faulkner’s Island and draw a line that passes just to the north side of the 2’ rock. Next, using parallel rules we would measure the bearing from the rock to the light.

Go for exercise order cheap levitra regularly- As you need to eat healthy and exercise regularly. In fact, gender differences touch almost every aspect of the energy industry, green and, in particular, brown. cialis online Continued Trust 20mg tadalafil seems to be a thing which is dying in New York. 29. Its supplements, available in different forms including 25mg, 50mg pharmacy online viagra and 100mg.

In our case 120°M. This 120°M bearing from the rock to the light is our Danger Bearing. To use it we have one thing left to do. We must determine whether a bearing greater than 120°M or one less than 120°m is safe. In this case any bearing on the light we take with our handheld compass that is greater than 120°m is safe so we would mark the bearing line we drew as NLT 120°m (NLT=Not Less Than). This label now tells anyone who looks at the chart that a bearing with our hand-held compass that is greater than 120°M is safe. If a bearing less than 120°M had been safe we would have labeled the chart NGT 120°M (NGT=Not Greater Than).

How can we determine whether the bearing should be labeled NLT vs NGT? By quickly taking another bearing. If you lay your rules on the rock itself or just to the south of the rock to the light on Faulkner’s Island the bearing you obtain would be less than 120°M and you would obviously sail over the rock. That tells us to stay safe any bearing we take must be greater than 120°M, anything less means we are standing into danger.

Now as we sail down our rhumb line of 133°M to ensure we are not be pushed by the tide into a dangerous situation we can take periodic bearings with the handheld compass on the Faulkner’s Island light, as long as the bearings we get are greater than 120°M we will miss the rock.

Chart 2

Danger Bearings along with a handheld compass are a quick and easy way to avoid a known hazard. Whenever you have a hazard near to your course and are concerned that tidal currents or leeway may sweep you in the direction of that hazard then the use of a Danger Bearing is appropriate. Danger Bearings can be obtained using both paper charts and Chart Plotters.

By creating a route between WP122 and WP120 we get a danger bearing of 120°M

On a chart plotter place a waypoint near the landmark one that would allow you to safely pass the hazard if you were sailing close by. (see chart 2) Now make these two bearings a route where you are sailing from the hazard to the landmark. In this case we want the bearing from WP122 to WP120, by making this a route we see that the bearing from WP122 to WP 120 is 120°M, our Danger Bearing. All that is left to determine is whether bearings Greater Than or Less Than the Danger Bearing are safe.

I’ve used a number of chart plotters, some show a line out ahead of my boat that I will traverse at my present course over the bottom, some do not. When that line isn’t present or If I have any doubts, I find it pretty easy to pick up the handheld compass and take a quick bearing that gives me piece of mind that I am standing clear of a hazard. The Danger Bearing is a quick and reliable method of staying out ahead of your boat and staying off the rocks, it should be a part of every mariner’s bag of navigational tricks!

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.